The following document sets out my thoughts on the current ecological problems facing Lough Neagh. This is both to address legitimate concerns and irresponsible misinformation regarding sand extraction and ownership of the bed and soil of Lough Neagh. I also want to bring more clarity on my views to the complex debate as to how best to secure the long-term health of the lough.

Background

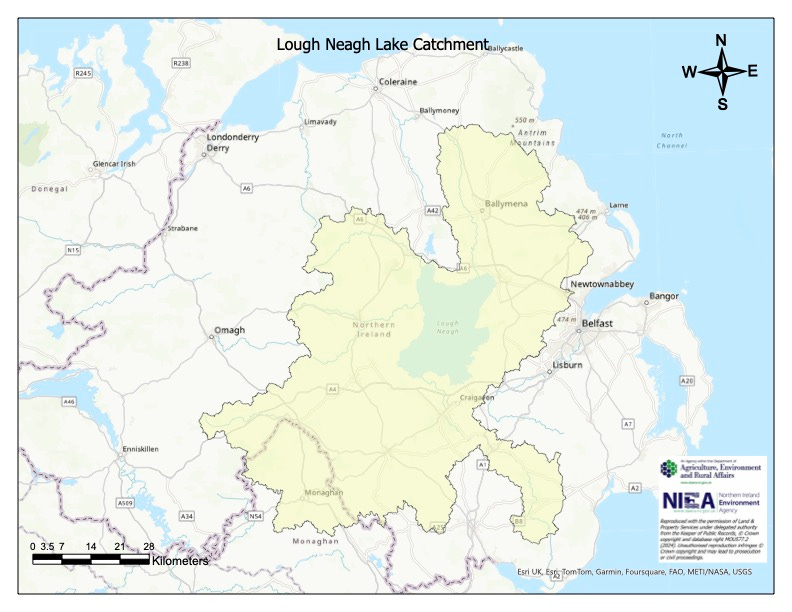

Lough Neagh is the largest freshwater lake in the UK covering an area of 383km2. Its catchment area covers about 43% of Northern Ireland[1] and over 80% of this land is agricultural.[2] It also provides approximately 40% of Northern Ireland’s drinking water.

Source: DAERA NI

In 2023 the build-up of nutrients in the lough led to devastating blue-green algae blooms[3]. The Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) released a statement on their website explaining the causes of this:

“The underpinning drivers of the increase in blue-green algae blooms include the excess nutrients from agricultural and wastewater systems within the Lough Neagh catchment, combined with climate change and the associated weather patterns, with the very warm June, followed by the wet July and August to date. This has been exacerbated by factors such as zebra mussels, which are upsetting the ecological balance in the lough.”[4]

Understandably, there has been widespread shock and concern about the current environmental crisis and demands for action. Poor water quality has been a known issue in Lough Neagh for decades. In 1967 a similar algae bloom occurred due to pollution.[5] In 2002, the Lough Neagh Advisory Committee produced a set of recommendations in their “Lough Neagh Management Strategy” (2002-2007) and identified the water status as “Hypertrophic - 145 micrograms phosphorus per litre”.[6]

The recent BBC spotlight documentary “Lough Neagh Monster” [7], which aired on 4th June 2024, revealed the shocking levels of pollution entering Lough Neagh. It also highlighted the failure of government to control and regulate the polluters.

For many years, I (along with others) have been calling for an independent management body to have legal oversight over the lough and the policies that impact it so issues such as pollution and water quality can be tackled.[8] [9]

Given the size of the lough, its catchment area, and the huge number of stakeholders involved, solutions will take time and recovery will require significant investment.[10]

A recent webinar (22nd April 2024) entitled “Lough Neagh: Past, Present and Future” chaired by Dr. Ewan Hunter, Head of Fisheries and Aquatic Ecosystems Branch at Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI), presented some of the long-term data on Lough Neagh. It revealed the processes, pressures and drivers of change in the lough over the last several decades as well as highlighting the challenges for recovery.[11]

In my role as director of the Shaftesbury Estate of Lough Neagh Ltd, a company that owns the rights to the bed and soil of Lough Neagh, I want to play my part in helping find solutions. Clearly, this cannot be solved by one person or entity alone. It needs collective action and a coordinated approach with community, government and private sector coming together.

There is good work already being done by various stakeholders including the Lough Neagh Partnership through the Resilience Project[12], research by AFBI and recommendations are currently awaited from the much-anticipated report on Lough Neagh by The Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA)[13].

In other areas that sense of collaboration is sorely missing and much needed. The crisis touches on many complex structural and emotive issues which require brave and innovative new ideas and approaches. It is important we do not waste this opportunity to build bridges and make the progress that is so desperately needed.

Target

Over the years I believe I have been used as a scapegoat for issues concerning the lough. I feel I am an easy target and a useful excuse for failings in proper governance. What Shaftesbury Estate of Lough Neagh Ltd does and doesn’t control is often misunderstood. As owners of the bed, the company has no control over the water in the lough nor any ability to control the nutrients that flow into it.

The company’s licensing of sand extraction has been used as evidence of environmental harm, but studies undertaken to date have shown no significant harm is caused by this activity in the location it is currently permitted.

Sand extraction licensed by the company is lawful and regulated, it occurs in an area less than 1% of the surface area of the lough. It has nothing to do with the causes of the blue green algae[14] and does not result in bird or insect decline (more details on the sand extraction are below). These issues are often deliberately conflated to criticise me personally and the company’s ownership.

I have always understood the sensitivities of my ownership in Northern Ireland. Since inheriting in 2005, I have repeatedly stated my willingness to explore different options for ownership as part of ongoing efforts to ensure a secure and sustainable future for Lough Neagh. I am acutely aware of the significance of the lough both culturally and environmentally, and its impact on the communities that live around it.

It has prompted me to discuss these issues and address criticism focused on the core themes of ownership, sand extraction and environmental harm. I also share my thoughts and aspirations about what I see as a path forwards.

The Ownership

I inherited the role as the 12th Earl of Shaftesbury unexpectedly in 2005. Despite this, I have always taken my responsibilities seriously and tried to navigate the role with humility. My family has owned the rights to the bed of Lough Neagh dating back to the 17th century. I recognise that Lough Neagh impacts the lives of many people and is a huge responsibility. I have not wanted to stand in the way of discussions over ownership and positive progress[15][16].

In 2012, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD) commissioned a Cross-Departmental Working Group to look at pursuing public ownership. This was following a Stormont debate brought by former Sinn Féin MP for Mid Ulster Francie Molloy, who claimed that public ownership would unleash the economic potential of the lough:

“The lough plays a significant role in the local economy, particularly through commercial eel fishing, sand extraction and the leisure facilities around it, but it could have greater tourist potential in the future. If properly utilised and developed, it could create substantial investment and much-needed employment opportunities. The development of any activity is at present curtailed because of the procedures that have to be gone through at Lough Neagh and with the Shaftesbury estate”[17]

The report produced by the Working Group in 2014 advised the government against acquiring the bed citing “no compelling grounds” for acquisition[18].

At that time, data from surveys taken with key stakeholders chosen by the Working Group, showed that 46% did not believe the lough should be brought into public ownership and only 30% believed it should. Furthermore, the report concluded: “…the Working Group has been unable to identify any tangible benefits in relation to the management of the lough which would accrue from Government ownership at this time of the bed and soil of the lough.”[19]

During 2016, Development Trusts Northern Ireland (DTNI), funded by DARD, looked at the possibility of setting up a community ownership trust “to acquire and strategically manage and operate Lough Neagh”. A series of interviews and public consultations were conducted, and I actively engaged in this process. More than 60 people, made up of different stakeholders attended a three-day workshop, entitled “The Future of Lough Neagh Its Potential - Our Shared Responsibility”, to explore the issues concerning the lough and generate ideas for its future. A follow-up report was published which recommended the establishment of an interim board for the new Lough Neagh Development Trust to take ideas forward.[20] However, despite this early promise the initiative sadly ran out of impetus and funding and the Trust currently remains dormant.

Given the huge number of stakeholders involved, including community groups, charities, government bodies, landowners, NGOs and multinational companies any transition to a new ownership structure is complicated.

A recent 2023 report by the Environmental Justice Network Ireland (EJNI) on Lough Neagh’s future ownership also presents the concept of Rights of Nature which may offer a solution for self-ownership of the lough itself.[21] This is a new approach that is gathering some momentum.

I explain this to help illustrate that the path to some form of alternative ownership structure has not been straight forward. Whilst many want public ownership the government, whose job is to represent the interests of the public, currently does not seem to want it.

Indeed, ownership does not even seem to be part of the upcoming DARD report on recommendations for Lough Neagh.[22] In a recent BBC Radio Ulster radio interview, Louise Cullen the BBC’s NI’s Agriculture & Environment Correspondent stated:

“Ownership I’m told does not form part of this plan simply because taking the lough into public ownership, and this has been acknowledged by so many people, just doesn’t solve any problems immediately. It actually could compound what is already a very complex and challenging situation to manage…”[23]

I have been open to exploring different ownership models for over a decade, and many options have been looked at and not pursued. This does not rule out other initiatives in the future and I remain committed to find a structure that will better suit the current challenges the Lough faces.

Whilst calls for me to “give it back” continue, the question remains: to whom? There is currently no entity that is offering to take it or who can guarantee to improve the environmental health of the lough. Despite this I remain open, willing and ready to engage on the future ownership structure of Lough Neagh.

The Profits

I have been accused of amassing huge profits from sand royalties and using these profits for the restoration of St.Giles House. No money from Lough Neagh has ever been used for any aspect of the restoration of St.Giles House. The clearest way to show this is by presenting 10 years of company profits from 2013-2022:

Shaftesbury Estate of Lough Neagh Ltd Financial Summary: (Profit After Tax)

2013: £ 7,164

2014: £ 35,777

2015: £ (21,004)

2016: £ (53,296)

2017: £ (241,519)

2018: £ 45,451

2019: £ 68,466

2020: £ 1,832

2021: £ 168,044

2022: £ 242,158

Total 10 Years: £245,918

Average: £24,591 per year

This data is publicly available on Companies House[24].

The restoration of St.Giles House happened primarily between 2011 and 2016 and was a significant project that was recognised by several national awards.[25] During this five-year period, the Shaftesbury Estate of Lough Neagh Ltd made £33k.

Sand Extraction: Background

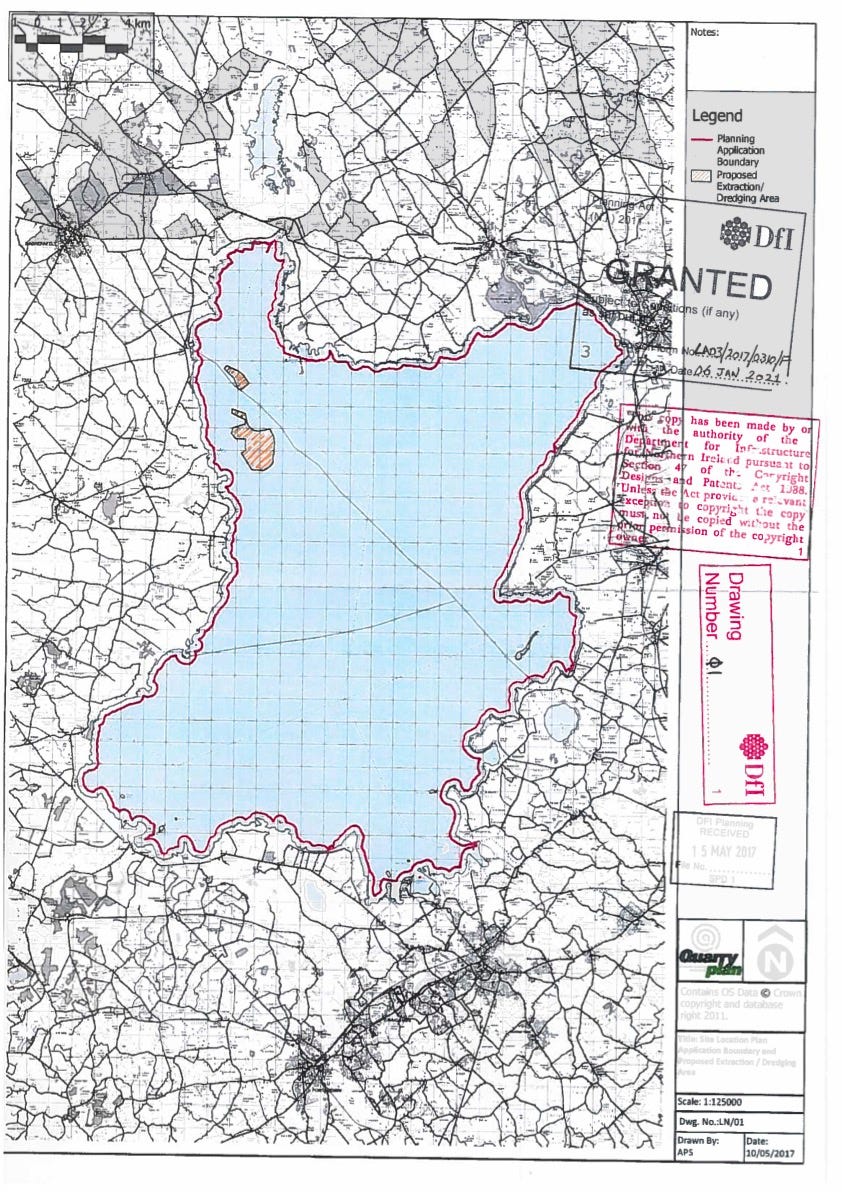

Sand extraction from Lough Neagh has been ongoing since the 1930s. Commercial grade sand is located in the Northwest corner of the lough. Extraction currently occurs in a 3.1km2 area which is less than 1% of the total surface area of the lough (total lough area is approximately 383 km2).

Source: Planning portal, site plan showing extraction area

There are five companies that hold licences that allow them to extract sand in return for a royalty, 50% of which goes to the Shaftesbury Estate of Lough Neagh Ltd and the remaining 50% goes to Northstone NI Limited. The licences run until 2046 and were in place before I became a director of the company in 2005. The licences require the companies to perform and observe all governmental regulations and requirements for such work (e.g. Ramsar (a Ramsar site is a wetland site designated to be of international importance), ASSI (Areas of Special Scientific Interest) and SPA (Special Protection Area)).

Planning permission for sand extraction was granted in January 2021 and lasts until May 2032 following a lengthy public hearing and a multi-year planning application process.[26] At that time, I gave an undertaking to the court to uphold the terms of their licence and enforce the cessation of sand extraction if permission was not granted. It is now tightly monitored by the The Department for Infrastructure (DFI) who charge a £30,000 annual monitoring fee to the sand extraction companies.

The permission limits the total amount of sand extracted to 1.5m tonnes per year. It also defines the areas of extraction and landing sites as well as a range of other conditions to effectively mitigate any potential harm. The British Geological Survey report provided as part of the planning application estimated there to be approximately 99.29m tonnes of commercial grade sand in the current location.[27]

Given that extraction and landing sand & gravel by the Lough Neagh Sand Traders (LNST) has been granted permission by the appropriate authorities I have no legal power to stop sand extraction. This would be the case whoever owned the bed of the lough, whether that be government or a community owned company. Sand extraction would only stop if the companies themselves decide to give up their licenses, or if they engaged in illegal activity or if they failed to comply with the conditions set out in their planning permission.

Lastly, unauthorised, and therefore completely unregulated and illegal sand extraction has been taking place in the lough for over a decade, despite repeated attempts by the Shaftesbury Estate of Lough Neagh Ltd to try to stop it. The matter is currently being dealt with by the courts and is well known to the authorising government departments, the local council(s) and the PSNI.

Whilst some are opposed to sand extraction in principle, viable alternatives are not obvious. Lough Neagh sand provides roughly 30% of the domestic sand requirements in Northern Ireland. Cessation would lead to an increase in provision of land-sourced sand and a higher carbon footprint to haul it. Shortages would lead to price increases, impacting the NI economy. There would also be the loss of around 247 local jobs (direct, indirect, induced).[28] Any debate on future extraction must be honest about these trade-offs when weighing up the decision of whether to continue or not.

Sand Extraction: Environmental Harm

Planning permission for sand extraction was based on a comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and was subject to a Habitats Regulation Assessment (HRA) to ensure the environmental designations of the lough were not compromised.[29]

Shared Environmental Services (SES), established to support councils across NI carry out their HRAs stated they were satisfied that future extractions, as proposed in the planning application, would not adversely affect the integrity of Lough Neagh and the Lough Beg SPA (Special Protection Area) and Ramsar site.[30] It was subsequently determined by the authority that sand extraction which complies with the conditions of the planning permission posed no threat to the designated features of Lough Neagh.

There is no evidence of any links between sand extraction and blue-green algae.[31] The latter is an issue affecting many lakes, rivers and shorelines across the UK and Europe. There is also no evidence of any link between sand extraction and declining populations of bird, fish or other species despite misinformation published online.

The Future

The current situation of the lough is deeply upsetting. There are many committed to finding solutions but currently there is a lack of a coordinated approach. The current crisis is too big for any one person or entity, it will require coordination and collaboration.

Over the last several months I have had encouraging discussions with representatives from National Trust, The Woodland Trust, NI Water, The Lough Neagh Partnership (of which Shaftesbury Estate of Lough Neagh Ltd. is a member), Friends of the Earth NI and a meeting with Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) Minister Andrew Muir MLA. There are still many stakeholders I would like to meet.

My belief is we need to work together to secure the lough’s long-term future. I am confident we can do that through good science, collaboration and a shared vision. There are now many landscape recovery projects using blended private sector and government finance to achieve ambitious restoration projects at scale, underpinned by robust data and research. These have seen farmers, landowners, charities and communities coming together for the sake of nature, with shared objectives and focused on a more sustainable future that embraces food production but in a regenerative way. I believe this is what is required and will be necessary to set Lough Neagh on a path to recovery.

I would like to transfer the ownership of the Shaftesbury Estate of Lough Neagh Ltd into a charity or community trust model, with rights of nature included, as I think that this could be the best way to support the long-term future of Lough Neagh. Reaching this may take time, and until another structure is created, I will continue to take my responsibility seriously and work hard with others to help bring about positive change. This includes, using company profits to invest in the future well-being of the lough and to work with others to seek solutions to the current problems.

[1] https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/publications/lough-neagh-catchment-map

[2] https://niopa.qub.ac.uk/bitstream/NIOPA/2806/1/an-evaluation-of-nutrient-loading-to-the-freshwater-lakes-estuarine-waters-and-sea-loughs-of-northern-ireland-nutrient-budget-and-simcat-analysis-2001-to-2009.pdf

[3] https://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2022-2027/2024/aera/0624.pdf

[4] https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/page/blue-green-algae

[5] https://www.antrimguardian.co.uk/news/2023/10/02/gallery/lough-shock-experts-were-aware-of-algae-threat-more-than-50-years-ago-46878

[6] https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=c1ef859bb87dfccbcbfb092b93e497bb03d34156

[7] https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m001zzfj/spotlight-the-lough-neagh-monster

[8] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-19840966

[9] https://www.belfastlive.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/earl-shaftesbury-issues-statement-after-28683310

[10] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c722jqeqd66o

[12] https://loughneaghpartnership.org/lnp-resilience-project

[13] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c722jqeqd66o

[14] https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/page/blue-green-algae

[15] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-68368769

[16] https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-19840966

[17] http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Assembly-Business/Official-Report/Reports-11-12/17-April-2012

[18] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-27726721

[19]https://www.niassembly.gov.uk/contentassets/49f353cd0e65462589f6960391aecfc8/20231023_appendix-b.pdf

[20] https://www.dtni.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/DTNI-Lough-Neagh-Report.pdf

[21] https://ejni.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/EJNI-Briefing-Sept-23-Lough-Neagh-Future-Ownership.pdf

[22] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c722jqeqd66o

[23] https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m00202pk

[24] https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/NI005979

[25] https://www.pha-building-conservation.co.uk/projects-wimborne-st-giles-house.htm

[26] https://planningregister.planningsystemni.gov.uk/application/149284

[27] Environmental Impact Statement, Geology (4.5.2): https://planningregister.planningsystemni.gov.uk/application/149284

[28] Oxford Economics, “The economic contribution of Lough Neagh Sand Traders 2017” https://planningregister.planningsystemni.gov.uk/application/149284

[29] Environmental Impact Statement, Ecology (7.10.13): https://planningregister.planningsystemni.gov.uk/application/149284

[30] Lough Neagh PAC Section 26 Report (63) https://planningregister.planningsystemni.gov.uk/application/149284

[31] https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/page/blue-green-algae